1 Why math? Why R?

1.2 The narrow focus of this course

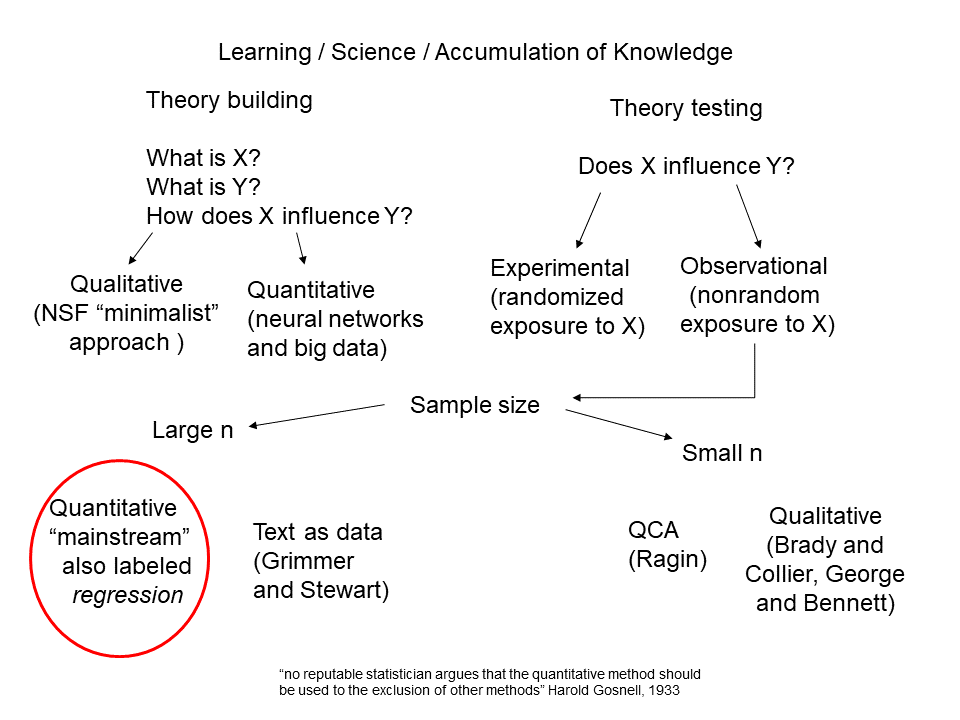

Simply put, the focus of this course is the statistical model. We won’t be looking at formal models or simulations. We will start with a simple, linear model and advance to more complex models that widen the range of things we can predict (to binary choices, counts, durations, or data observed over time). The place of all of this in the broader research enterprise can be difficult to understand. Think of all of the ways that you could learn by observation - a statistical model is just one approach among many and is most useful only if a number of assumptions or conditions are satisfied. The graphic below places this effort in the broader context of our research enterprise, differentiating what we do in this class from qualitative work and from theory-building work. My approach to statistical modeling centers on theory-testing with large (or at least not small) samples, sometimes randomly generated. Note that a comparative case study, for instance, might employ any of these tools - theory-building and theory-testing, quantitative or qualitative, text or numbers as data - so labeling something a comparative case study doesn’t tell you what type of approach you are taking.

Figure 6. How does regression fit in?

The works cited in the figure are representative and you have probably run across them in other courses.

This course is also almost entirely located in the frequentist statistical tradition, since almost all of the work you read in the literature uses these tools. I will introduce Bayesian tools and there is a course and text in the Bayesian tradition that you might take a look at it on your own “Rethinking Statistics” (McElreath 2020). That course also emphasizes how causal models precede and inform statistical models, why documentation and coding is both useful for you and vital for replication. You can find his lectures on YouTube: check out the first lecture - golems, owls, and DAGS.

1.3 Why use R?

In order to build your understanding of statistical modeling, we will use the statistical software R. Why?

R is free

R is flexible

R is supported a user community dedicated to the idea of open source

R is transportable – you can easily take what you learn for one project and apply it to another

R is reproducible – this is key

1.4 How R works

Commands in R create and use what are known as objects. An object could be a single number, a column of numbers (a vector), a matrix, or a matrix that is identified as data (a data frame sometimes abbreviated df). Objects are named by you when they are created.

Commands in R use functions to take input and produce output. There are many functions packed in the base R installation, but we are some specialized functions that we need to add. These specialized function are published in packages that you can install on your PC. When you use a function from a package, you must first make that package visible to R with the library function

The typical structure of an R command is

object <- function()You can chain together several functions with a pipe, %>%, so you might see many lines of commands linking together to generate one new object.

1.5 Three examples

Comparing groups. Turnout in the 2016 presidential election

The Current Population Survey is a US Census product that is based on a monthly survey of ~60,000 people living in the United States. The primary use of the CPS is to measure the monthly unemployment rate. In 1960 the Census began to include a supplement each November that recorded whether not someone voted. Since the survey is so large, we can use it to generate reliable estimates of turnout for small groups.

# Any lines that start with a # are just comments, notes to myself so I can recall why I made particular choices. I use comments liberally.

# Use the read_fwf function from the read_r library

# Read the data from the CPS raw data file

# I used the codebook to identify the variables and column numbers

# We can take a look at the codebook in class.

# This is really tedious work, and potentially introduces errors

cps16<- read_fwf("data/nov16pub.dat", fwf_cols(

hrinsta=c(57,58),

prtage=c(122,123),

pemaritl=c(125,126),

sex=c(129,130),

ptdtrace=c(139,140),

pehspnon=c(157,159),

prpertyp=c(161,162),

penatvty=c(163,165),

pemntvty=c(166,168),

pefntvty=c(169,171),

prcitshp=c(172,173),

prinusyr=c(176,177),

weight=c(613,622),

prnmchld=c(635,636),

vote=c(951,952)),

col_types = cols()

)

# Filter to include only citizens 18 and older

# The filter function just keeps a subset of observations in the new object

# Notice the use of a pipe %>%

# This requires the dyplr library

cps_valid<- cps16 %>% filter(hrinsta==1 & prtage>=18 & prpertyp==2 & prcitshp!=5)

# Recode to treat people who refused or did not answer as not voting

# This is the dplyr recode function

cps_valid$turnout<-recode(cps_valid$vote, '-9' = 0, '-3' = 0, '-2' = 0, '2' = 0, '1' = 1)

# Create new variable race and make it a character (a categorical variable)

# Notice that I am reading from and writing to the same data frame

# murate is the function to create a new variable from an existing variable

cps_valid<- cps_valid %>%

mutate(

race = case_when(

ptdtrace==1 & pehspnon!=1 ~ "White, not Hispanic",

ptdtrace==2 ~ "African American",

ptdtrace==4 ~ "Asian",

ptdtrace==1 & pehspnon==1 ~ "Hispanic",

TRUE ~ "Other"

)

)

# Create an R object that summarizes turnout by race

# the .groups option, included here, suppresses a warning message that doesn't apply with a single grouping variable

# group_by is a function

# summarize is a function

d<- cps_valid %>%

group_by(race) %>%

summarize(turnout = 100*weighted.mean(turnout, weight, na.rm = TRUE), count=n(), .groups = 'drop')

# Produce a table with the kable function and include options to customize column names, add a title, limit to two digits after the decimal point.

kable(d, digits = 2, caption = "**Table 1. Turnout, by race, 2016 US presidential election**", col.names=c("Race", "Turnout", "Count"))| Race | Turnout | Count |

|---|---|---|

| African American | 59.42 | 9834 |

| Asian | 49.04 | 3794 |

| Hispanic | 47.16 | 7899 |

| Other | 49.05 | 3103 |

| White, not Hispanic | 65.30 | 69164 |

You can see the turnout among White voters was much higher than any racial or ethnic minorities, one component of Donald Trump’s victory and something that would change in 2020.

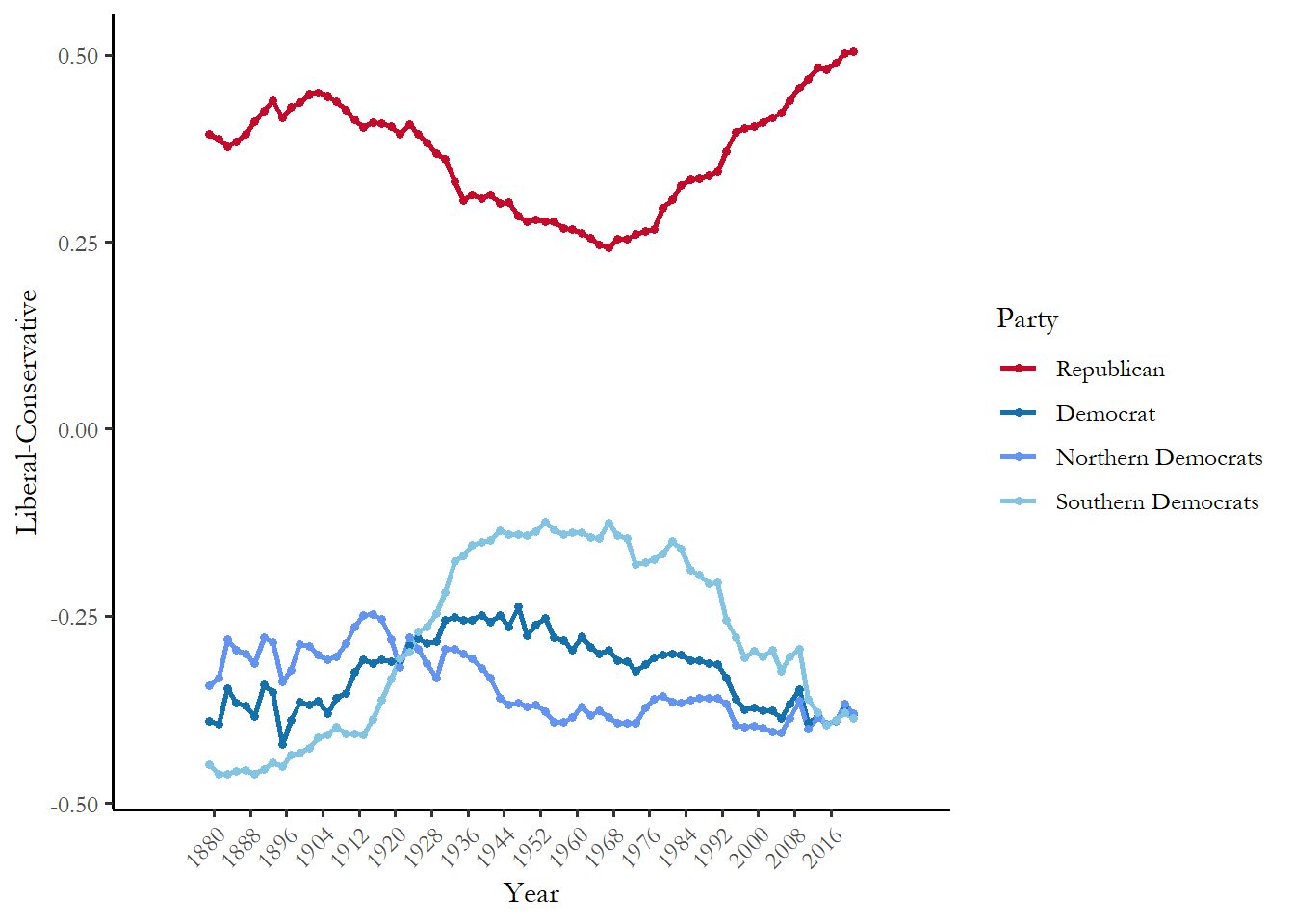

Creating figures. Ideological polarization in the U.S. House of Representatives

You may have encountered Poole-Rosenthal scores (also known as D-NOMINATE scores) in your reading on the US Congress. The scores use roll-call votes to measure the ideological position of members of Congress relative to other members. We can use these scores to track the ideological polarization in Congress. The figure below summarizes the mean Republican and Democratic member of the House of Representatives in each 2-year session.

# This code is from https://voteview.com/articles/party_polarization

# Note that I am reading the data from a website - you can run this chunk to replicate the figure

nom_dat <- read_csv("https://voteview.com/static/data/out/members/HSall_members.csv", show_col_types=FALSE)

south <- c(40:49,51,53)

# Added this to suppress a warning message

options(dplyr.summarise.inform = FALSE)

polar_dat <- nom_dat %>%

filter(congress>45 & chamber != "President") %>%

mutate(year = 2*(congress-1) + 1789) %>%

group_by(chamber,congress,year) %>%

summarise(

party.mean.diff.d1 = mean(nominate_dim1[party_code==200],na.rm=T) -

mean(nominate_dim1[party_code==100],na.rm=T),

prop.moderate.d1 = mean(abs(nominate_dim1)<0.25,na.rm=T),

prop.moderate.dem.d1 = mean(abs(nominate_dim1[party_code==100])<0.25,na.rm=T),

prop.moderate.rep.d1 = mean(abs(nominate_dim1[party_code==200])<0.25,na.rm=T),

overlap = (sum(nominate_dim1[party_code==200] <

max(nominate_dim1[party_code==100],na.rm=T),na.rm=T) +

sum(nominate_dim1[party_code==100] >

min(nominate_dim1[party_code==200],na.rm=T),na.rm=T))/

(sum(!is.na(nominate_dim1[party_code==100]))+

sum(!is.na(nominate_dim1[party_code==200]))),

chamber.mean.d1 = mean(nominate_dim1,na.rm=T),

chamber.mean.d2 = mean(nominate_dim2,na.rm=T),

dem.mean.d1 = mean(nominate_dim1[party_code==100],na.rm=T),

dem.mean.d2 = mean(nominate_dim2[party_code==100],na.rm=T),

rep.mean.d1 = mean(nominate_dim1[party_code==200],na.rm=T),

rep.mean.d2 = mean(nominate_dim2[party_code==200],na.rm=T),

north.rep.mean.d1 = mean(nominate_dim1[party_code==200 &

!(state_icpsr %in% south)],na.rm=T),

north.rep.mean.d2 = mean(nominate_dim2[party_code==200 &

!(state_icpsr %in% south)],na.rm=T),

south.rep.mean.d1 = mean(nominate_dim1[party_code==200 &

(state_icpsr %in% south)],na.rm=T),

south.rep.mean.d2 = mean(nominate_dim2[party_code==200 &

(state_icpsr %in% south)],na.rm=T),

north.dem.mean.d1 = mean(nominate_dim1[party_code==100 &

!(state_icpsr %in% south)],na.rm=T),

north.dem.mean.d2 = mean(nominate_dim2[party_code==100 &

!(state_icpsr %in% south)],na.rm=T),

south.dem.mean.d1 = mean(nominate_dim1[party_code==100 &

(state_icpsr %in% south)],na.rm=T),

south.dem.mean.d2 = mean(nominate_dim2[party_code==100 &

(state_icpsr %in% south)],na.rm=T),

)

polar_dat_long <- polar_dat %>% gather(score,value,-chamber,-year,-congress)

labels <- c("dem.mean.d1"="Democrat",

"rep.mean.d1"="Republican",

"north.dem.mean.d1"="Northern Democrats",

"south.dem.mean.d1"="Southern Democrats")

# This is based on the voteview RMD but modified so that it does not use ggrepel and is not a function

pdatl <- polar_dat_long %>%

filter(chamber=="House",

score %in% c("dem.mean.d1","rep.mean.d1",

"north.dem.mean.d1","south.dem.mean.d1")) %>%

mutate(Party=labels[score]) %>%

ungroup()

ggplot(data=pdatl,

aes(x=year,y=value,group=Party,col=Party)) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0.15, 0),

breaks=seq(1880, max(pdatl$year), by=8)) +

geom_line(size=1) + geom_point(size=1.2) +

xlab("Year") + ylab("Liberal-Conservative") +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1)) +

scale_color_manual(values=c("Republican"="#c70828",

"Democrat"="#1372ad",

"Northern Democrats"="#6194F4",

"Southern Democrats"="#81c4e4"))

Figure 7. Polarization in the US House of Representatives

You can see how the medians have diverged over time - Republicans become much more conservative and Democrats somewhat more liberal as the differences between Southern and Northern Democrats diminish. The data and R code are from the voteview website (Lewis et al. 2022)

Estimating a model. ANOVA with one variable

This is just an example using lm function (short for linear model). This is a linear probability model and we will learn alternative (and better) modeling strategies for this situation in week 4 (logistic regression). But I just wanted you to see that we can use lm to perform ANOVA (a regression with a categorical variable).

R recognizes race as a categorical variable and automatically creates a dummy variable with the baseline category as the first factor and compares that group to every other group.

# First I am using the factor function to make sure that White voters (the largest racial group) are the baseline category.

cps_valid$race2<-factor(cps_valid$race, levels=c("White, not Hispanic", "African American", "Hispanic", "Asian", "Other"))

# In this case I just produce the table and don't retain the model info

# lm estimates the model

# tidy formats the output so that we can use kable

# kable produces the table

temp<-tidy(lm(turnout~race2, weight=weight, data=cps_valid))

kable(temp, digits=3, caption = "**Table 2. Race and turnount, 2016, ANOVA**")| term | estimate | std.error | statistic | p.value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.653 | 0.002 | 344.216 | 0 |

| race2African American | -0.059 | 0.005 | -12.272 | 0 |

| race2Hispanic | -0.181 | 0.005 | -34.693 | 0 |

| race2Asian | -0.163 | 0.008 | -21.412 | 0 |

| race2Other | -0.162 | 0.009 | -17.959 | 0 |

We learn that White voters turnout at a bit higher rates than African Americans, but those two groups have substantially higher turnout than other racial and ethnic minorities. Note how the predicted values correspond to (match) the levels reported in Table 1.

In future classes we will work with the stargazer package to produce regression tables that are publication-ready.

1.6 Reproducing results - why is that important?

One the features of R that is powerful is the ability to share your research for replication. No one needs to have a proprietary or expensive piece of software or access to specialized resources to reproduce your work. Moreover, anyone with a working knowledge of R can inspect your programming to see exactly how you transformed or manipulated data, exactly the modeling choices you made, and how you evaluated the robustness of your choices. Other researchers can experiment with different approaches and improve the work over time. We will talk more about replication later in the term, but it is a good idea to cultivate a habit of meticulous recording of your work. I use comments and Rmarkdown files to do that.

Why can’t I use EXCEL?

EXCEL is very useful for data entry. But there are two major drawbacks to EXCEL for research. First if you share data in EXCEL, then many people without access to that software can’t review your work. And as Microsoft changes EXCEL over time, your data may become unreadable to people with newer versions. We would like to avoid this software dependence. R markdown files are simply text files, so anyone can look at them. And most replication archives encourage you to submit and store your data in the same form - as a text file anyone can read. You will learn how this works as we learn about the Harvard Dataverse in future classes.

Another drawback of EXCEL is the potential for errors. You can’t see how a cell value is calculated without inspecting each cell, so it would be tedious to do that and a corrupted cell or typo could lead to an error. There is also the potential for mismatching records when you merge data from different sources. And cut-and-paste errors. And you really can’t do any or much of the statistical analysis in EXCEL, so you will end up reading the data into statistical software anyway.

Think this sounds far-fetched? There was a very recent and very public error by a pair of influential economists. One short account The Reinhart-Rogoff error – or how not to Excel at economics describes the error and implications. What happened?

Reinhart and Rogoff’s work showed average real economic growth slows (a 0.1% decline) when a country’s debt rises to more than 90% of gross domestic product (GDP) – and this 90% figure was employed repeatedly in political arguments over high-profile austerity measures….in their Excel spreadsheet, Reinhart and Rogoff had not selected the entire row when averaging growth figures: they omitted data from Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada and Denmark. In other words, they had accidentally only included 15 of the 20 countries under analysis in their key calculation. When that error was corrected, the “0.1% decline” data became a 2.2% average increase in economic growth.

So it is fine to use EXCEL to record information, but once you have a snapshot of the raw data preserved as a text file, all of the manipulations, transformation, and modeling should be done in a way that is transparent and reproducible - and R works for that purpose.

1.6.1 Note on qualitative methods

A recent issue of Perspectives on Politics introduced a really important set of documents and discussions: The Qualitative Transparency Deliberations. Here is short summary from the article:

In recent years, a variety of efforts have been made in political science to enable, encourage, or require scholars to be more open and explicit about the bases of their empirical claims and, in turn, make those claims more readily evaluable by others. While qualitative scholars have long taken an interest in making their research open, reflexive, and systematic, the recent push for overarching transparency norms and requirements has provoked serious concern within qualitative research communities and raised fundamental questions about the meaning, value, costs, and intellectual relevance of transparency for qualitative inquiry.

The short article presents findings from a much larger set of reports by several working groups that, together, give a very good sense of the scope of qualitative work in Political Science and some of the questions about qualitative research practice that political scientists confront. The entire collection is available at this link:

You could construct a semester-length seminar on just the first report. We will take a look, but if you plan to adopt a qualitative approach for your own work, it would make sense to read this report, learn about this work.

1.7 Next week

One common misconception about statistical models is that they are only really useful for applications to political behavior, particularly analysis of survey data. This doesn’t describe the way the models have been applied in Political Science and, in particular, ignores the recent proliferation of statistical and experimental work in public policy evaluation. We will spend a week talking about learning from data, with a particular focus on learning about how government programs perform. The assignment due before class is loosely structured, designed to get you to think about the potential for this work, practical and ethical challenges, and some of the reasons why evidence-based policy-making has emerged as a powerful tool, particularly in the last decade.

Social Security Administration Office of Chief Actuary

The SSA produces an annual estimate of the balance in the OASDI trust funds - the money available to make up the shortfall between Social Security revenues (FICA tax collections) and Social Security expenditures (payments to elderly or disabled recipients). These estimates factor in demographic and economic assumptions about mortality, fertility, immigration, economic growth, inflation, interest rates and other data that might impact future claims and future revenue. The estimates are summarized for three different scenarios - media coverage typically focuses on the intermediate assumptions (II). I is the “low-cost” scenario and III is the “high-cost” scenario.

Figure 5. Screenshot from Social Security Board of Trustees (2020)

You can see that combined Trust Funds are likely to be exhausted by 2035.